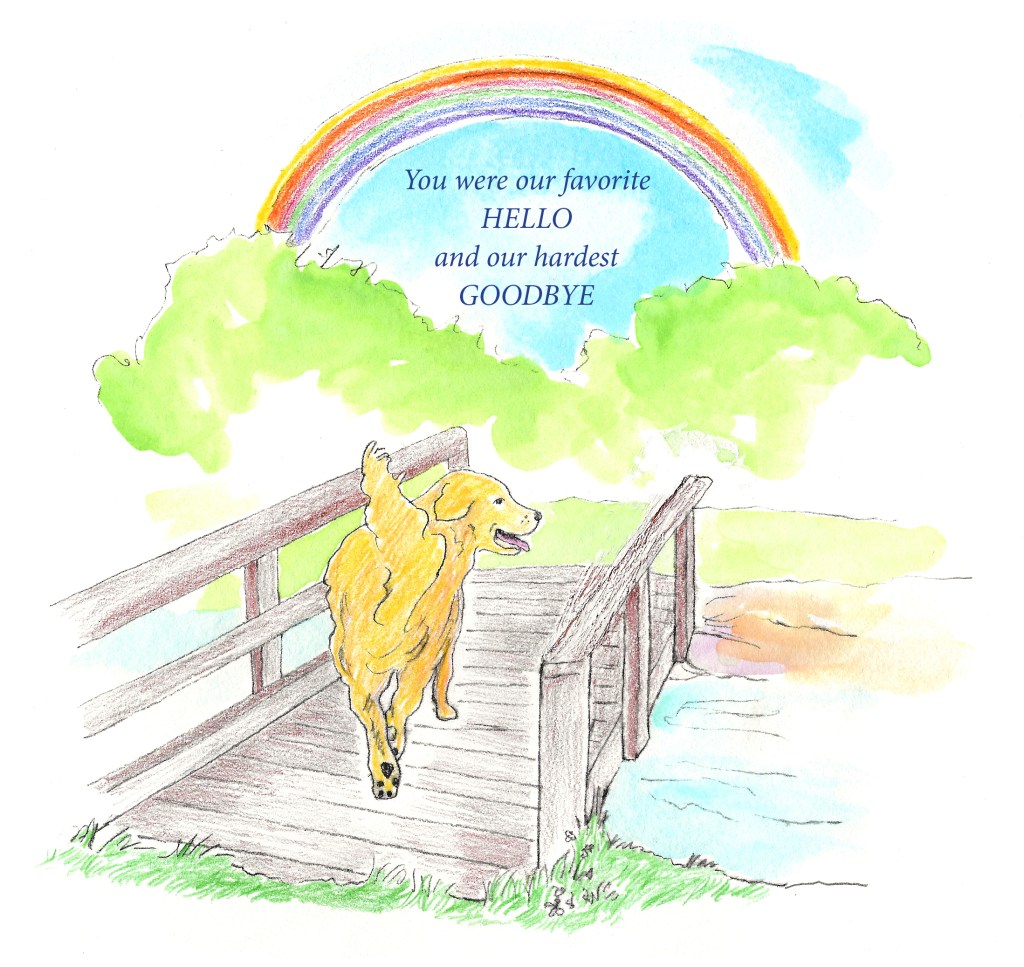

I almost missed that today is Rainbow Bridge Day or more correctly Rainbow Bridge Remembrance Day. Rainbow Bridge Remembrance Day is a day of reflection and gratitude that takes place every year on August 28th to honor pets who have passed away. We lost several pets through the years, hamsters, snakes, rabbits and dogs. In this post I will focus on the dogs we lost including Daisy our Pug, Bronco our Leonberger, Ryu our Japanese Chin, Baby our German Shepherd and Baylor or Labrador, or rather Yellow Lab mix. I will start with the dog we lost last, our Pug Daisy and end with the dog we lost first, our Labrador Baylor. I should say that my wife had dogs before we met each other, but Baylor was my first dog. I did not grow up with dogs. We miss them all very much. They left a hole in our hearts.

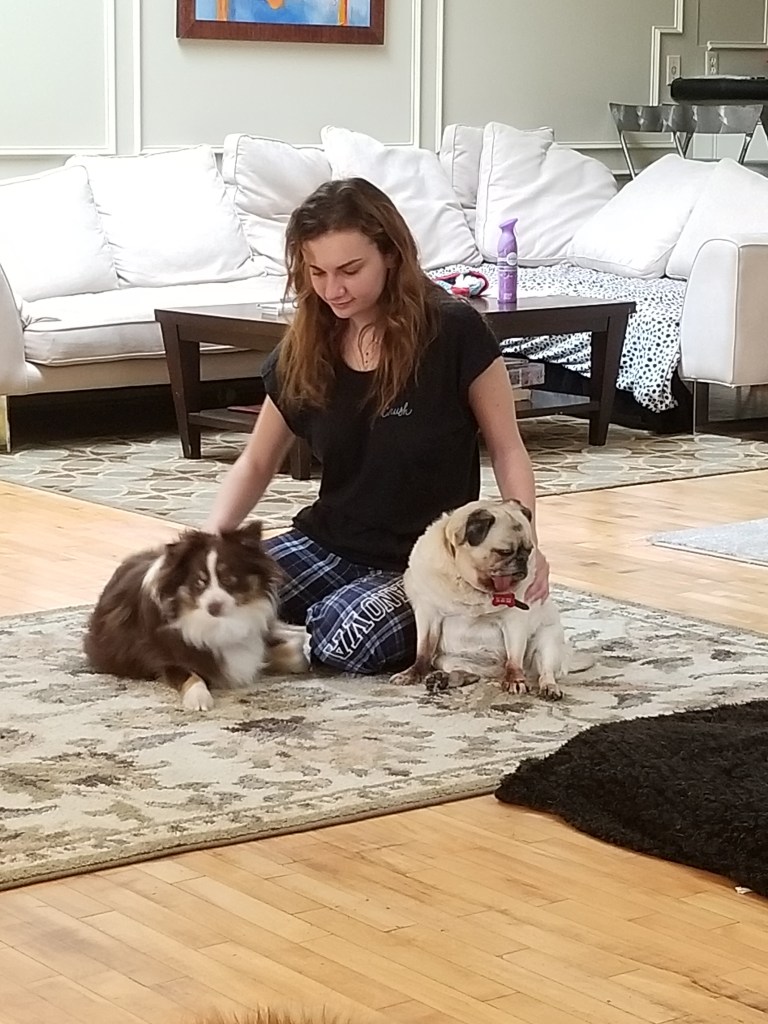

Our Pug Daisy was a sweet and easy dog who lived a long life. On April 5th this year she died peacefully in our arms at the age of 15 ½ years old. This was just a few months ago, and it still feels strangely empty without her. Our dog Rollo, a mini–Australian Shepherd has been alone ever since.

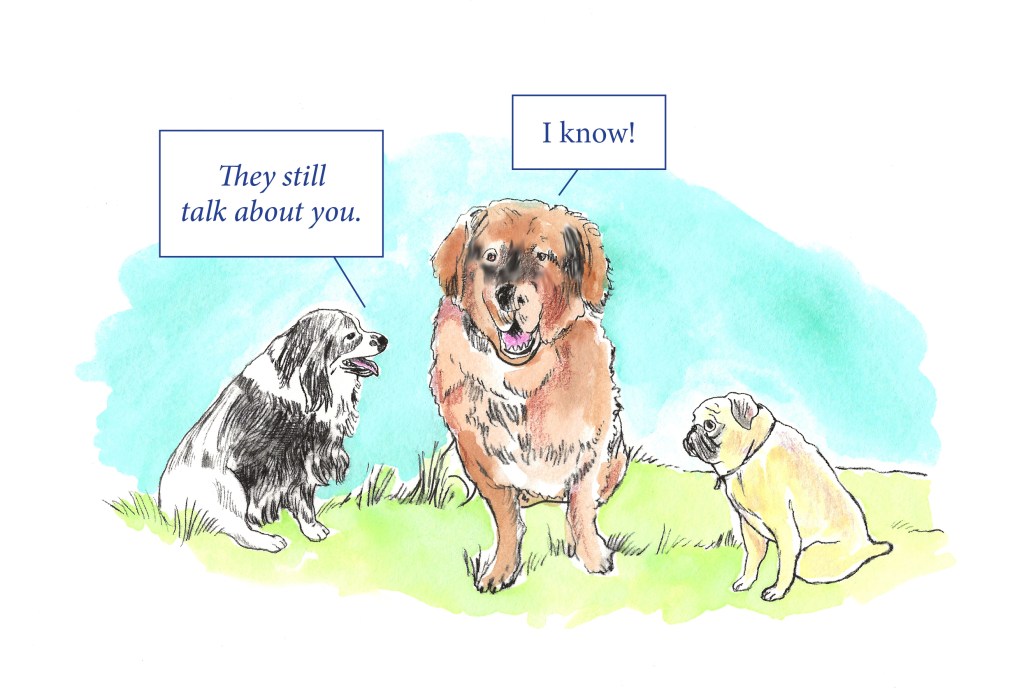

The dog we lost before Daisy was our Leonberger dog Bronco. The Leonberger dog is a very large dog related to St. Bernards, Newfound land dogs, and Great Pyrenees, He died on June 16, 2020, just a couple of weeks before his 13th birthday. He lived a long life for a Leonberger. He was s sweetheart who protected our smaller dogs. He likely saved the life of our other dogs a couple of times, he found run-away hamsters, and he saved our neighborhood from a nightly intruder harassing the women in the neighborhood. He was also incredibly funny. I wrote a book about him and the Leonberger breed. Look to the right if you are using a laptop and at the bottom of the screen if you are using a mobile phone.

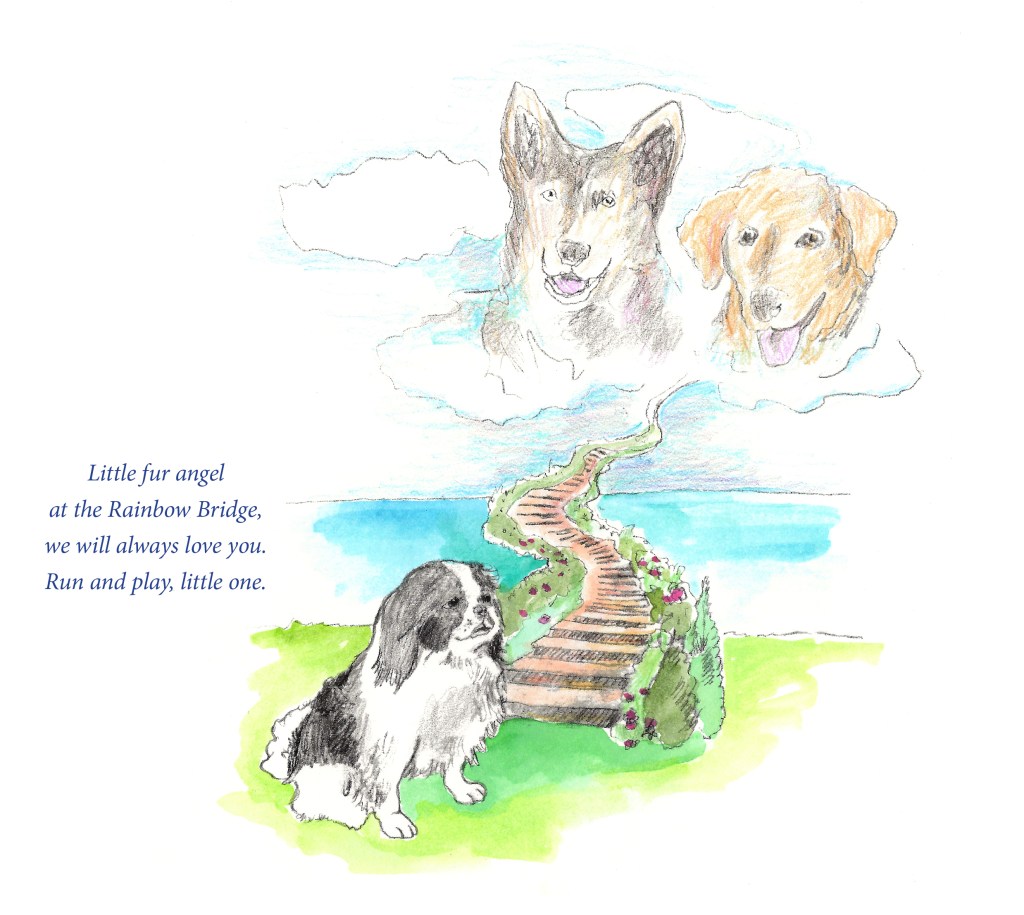

In February of 2018 we lost Bronco’s little friend our little Japanese Chin Ryu. We bought him from Petland not knowing that they got their dogs from Puppy Mills. One time when we went to Petland to buy dog food we brought Ryu with us. As we approached the store he started shaking out of fear. That was a wakeup call for us. He loved howling and it sounded like he was singing an opera. Perhaps he loved howling for the attention he got when he did. Everyone turned around and clapped when he howled. He was a happy fella who died a bit prematurely at the age of 10 from cancer. I was working 16-hour days in Oklahoma when he passed so I could not be with him when he died, which is something I will forever regret.

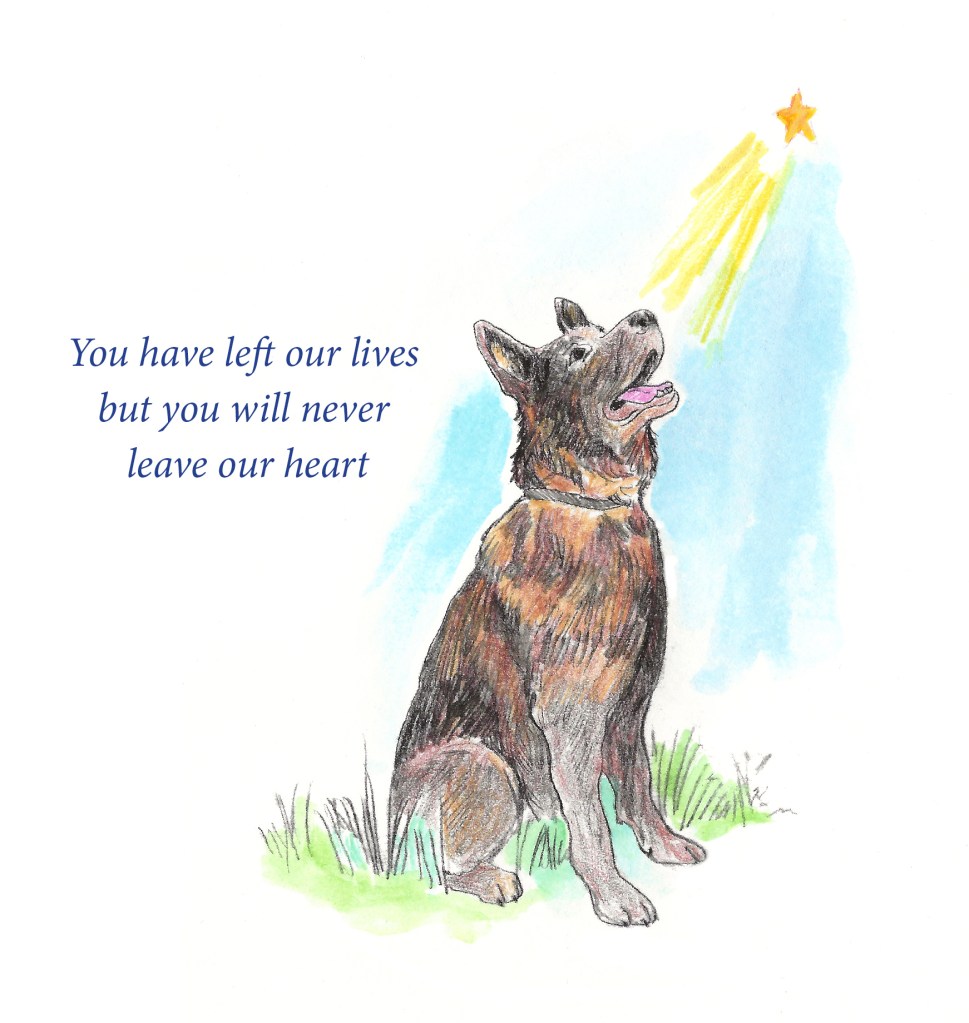

Baby was a female German Shepherd. One of Claudia’s sisters had rescued her. We were told she had been abused by her first owners and she was a very anxious dog. We frequently took the dogs to the dog park, but she was never comfortable there and kept to herself. She was very protective of our Leonberger Bronco when he was a puppy. She played with him and protected him fiercely as if she was his mother. She died from cancer at home on her mattress. It would have been better for her to get an injection at the veterinary, but we did not react quick enough. Another thing we regret.

Baylor was a ¾ Yellow Lab and ¼ Ridgeback. He was a happy and brave dog who fought bravely when attacked by other dogs. He was also food crazy and stole a lot of food. As he got older, he developed diabetes and cataracts. His passing was the saddest and most shocking. We had left our dogs with a dog sitter during a ski vacation when she called us and told us she could not stay at our house because she had several other dogs to take care of. Something she had not told us. We were forced to allow her to take our dogs to her house. The next phone call was much worse. She had put Baylor out in her backyard because he was barking at night, and he had escaped. It was a cold night. He was found dead the next morning halfway between her house and our house. Hit by a driver who just left him there. Apparently, he had tried to get back to our house. It was quite a shock, and the kids were bawling their eyes out. That was the last time we hired a dog sitter.

All illustrations are by Naomi Rosenblatt